Nitrous Oxide: Will It Blow Up Your Engine?

Nitrous oxide has been immortalized in car flicks for decades, and for good reason: the stuff works and the word “nitrous” sounds cool. Hot rodders have been using it on their engines to make big increases in power and torque since the late 1950s.

But there are many factors to consider before you install a nitrous oxide system on your car. If you use the right type of system for your goals and follow the system manufacturer’s instructions, it’s possible to safely run nitrous on your engine. But like all power adders, nitrous isn’t without risk.

Read on to learn how nitrous oxide boosts power and how to avoid damaging parts when applying nitrous to your engine.

More Oxygen Unleashes More Power

Significantly increasing the performance of an engine requires cramming more oxygen into its cylinders. Turbocharging and supercharging achieve this by compressing ambient air. Nitrous oxide systems introduce an oxygen-rich compound directly into the engine’s intake system. For comparison’s sake, nitrous oxide is 36% oxygen; ambient air is 21% oxygen. Whether by forced induction or nitrous, the increased oxygen concentration allows additional fuel to be burned, resulting in more power.

Nitrous is cheaper and easier to install than forced induction, but it’s power boost is temporary. Your fun lasts only as long as the nitrous bottle is big. Once it runs dry, you’re back to stock engine power.

Currently it costs about $50 to refill a 10 lb. bottle, which will last about 8-12 quarter mile passes depending on the size of your jets.

How Much Nitrous is Too Much?

In a nitrous system, nitrous oxide is stored as a pressurized liquid in an aluminum or carbon fiber tank mounted somewhere in the car, usually in the trunk. The liquid is routed to the intake manifold through a series of lines, valves and fittings. When it reaches the engine’s intake, the liquid turns into a gas which is then drawn into the cylinders. This vaporization process cools the intake air, further increasing performance.

Nitrous oxide’s power potential is proportional to how much of the stuff you pump into the engine. Like carburetors, nitrous nozzles have jets that can be swapped out to inject more or less nitrous. Use a small jet for a small bump (or “shot”) in power, or a large one for as much power as your confidence in the engine’s ability to handle it allows.

The answer to the question “How much nitrous is too much?” depends on your engine and the strength of its block and internal parts like its pistons and connecting rods.

Performance increases generally range from 25 to 500 horsepower. But don’t get greedy, no stock engine will take kindly to a 400-hp shot of nitrous. If you plan to run more than 100-hp shot you’ll probably need to beef up your internal engine parts with stronger hardware designed for nitrous boosted applications.

Wet and Dry Nitrous Systems

There are two major types of nitrous systems – “wet” and “dry.” In wet systems, the fuel and nitrous oxide are combined at the point (or points, if a direct port system) where they are dispersed into the engine’s intake, and the delivery of both is synchronized by a single control system. Dry systems introduce only the nitrous oxide itself; the additional fuel must be handled separately.

There are pros and cons to both types.

- Carbureted engines are most commonly fed with a nitrous plate that mounts between the carburetor and the intake manifold. These wet systems have spray bars that direct nitrous and fuel into the manifold, but carburetors are relatively inflexible when it comes to adding more fuel on demand.

- Electronic fuel injection engines with programmable controls are better able to drastically increase the fuel flow rate when the nitrous is switched on, making a dry nitrous system more viable.

Whether wet or dry, it is imperative that sufficient fuel is added with the nitrous. If not, the resulting lean air/fuel mixture can lead to aggressive detonation or “knocking” that will damage the engine’s internals. Even the most capable knock control system will struggle to manage the knocking induced by a nitrous system that’s operating lean.

Single Nozzle Nitrous Systems

The simplest and least expensive type of nitrous delivery system is a single-nozzle system, which has the fewest parts. Single-nozzle systems can be wet or dry. The nozzle is typically mounted in the intake tract well upstream of the throttle body to maximize the chances of the nitrous mixing thoroughly with the incoming air.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to know whether each cylinder is getting the same amount of nitrous. If the mixing is incomplete, there will be an uneven distribution of nitrous among the cylinders. One cylinder will get a lot more than others, making that cylinder much leaner than the rest.

These mixing limitations mean single-nozzle systems are best suited to small shots of nitrous in the 30-100 horsepower range.

Direct Port Nitrous Systems

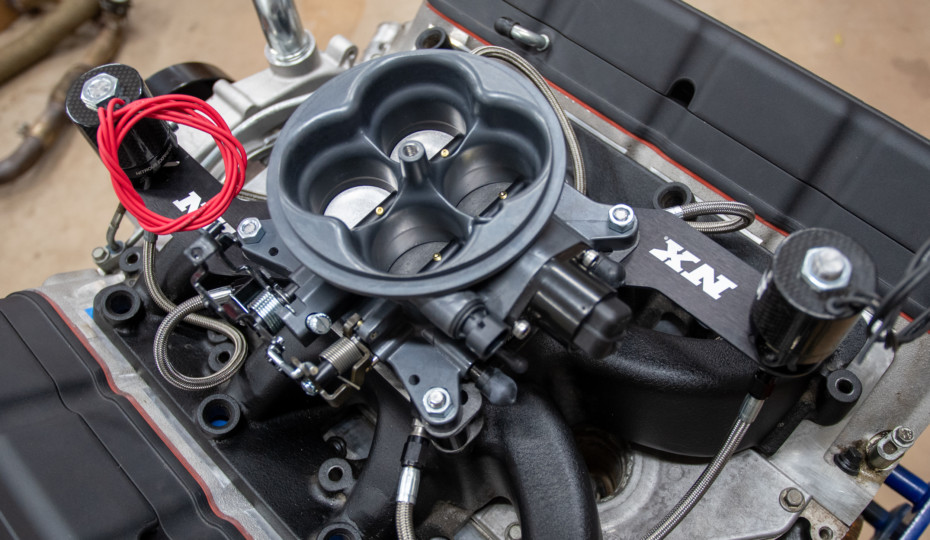

Ensuring proper distribution is the name of the game for direct port nitrous systems. These systems mount a wet or dry nitrous nozzle in each runner of the intake manifold. The beauty of direct port systems is their tunability. The nozzle jets can be fine-tuned on a per-cylinder basis to suit the airflow differences that each cylinder experiences.

Direct port systems are more complex and require more labor to install. But they are undeniably the best and most capable type when it comes to power and engine longevity, especially with larger nitrous shots.

Still have questions about installing a nitrous kit on your engine? Speak to one of our Tinker Experts today!

***Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are ours and not those of any other organization. Using nitrous oxide in engines can potentially cause damage and is subject to regulations by the EPA and ARB. Please do your own research and consult professionals before using nitrous oxide in your vehicle. We are not responsible for any actions taken based on our blog.